Transforming Perioperative Care for People with Diabetes Undergoing Elective and Emergency Surgery

Consultant Anaesthetist, Clinical Lead CPOC Diabetes Working Group

Consultant Geriatrician, CPOC Deputy Director

The new CPOC guidelines for perioperative care for people with diabetes undergoing elective and emergency surgery were launched on 03 March 2021 at the CPOC webinar. These guidelines are the first in the suite of guidelines to be produced by CPOC. Future guidelines will cover perioperative anaemia and frailty.

These guidelines were born out of the NCEPOD’s (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death) confidential enquiry and review of the quality of care provided to patients with diabetes who underwent a surgical procedure. The report “ Highs and Lows” identified good pockets of care, as well as areas that could be improved. It identified several key recommendations, not least the need for a national joint standard and policy for the multidisciplinary management of patients with diabetes who require surgery. CPOC was tasked with producing this national standard.

Whilst there are similarities to the previous guidelines on the perioperative management of diabetes, this guidance overcomes the short comings of the previous guidance. It is more multidisciplinary and now includes authors from the specialities of primary care, pharmacists, geriatric medicine, diabetes inpatient specialist nurses, patient representatives in addition to diabetologists, surgeons and anaesthetists. There is more detailed discussion on the perioperative management of wearable technology namely insulin pumps (continuous subcutaneous insulin infusions). Probably most importantly there are sections to ensure implementation of the guidance. Guidance will only improve patient care and outcomes if it is implemented.

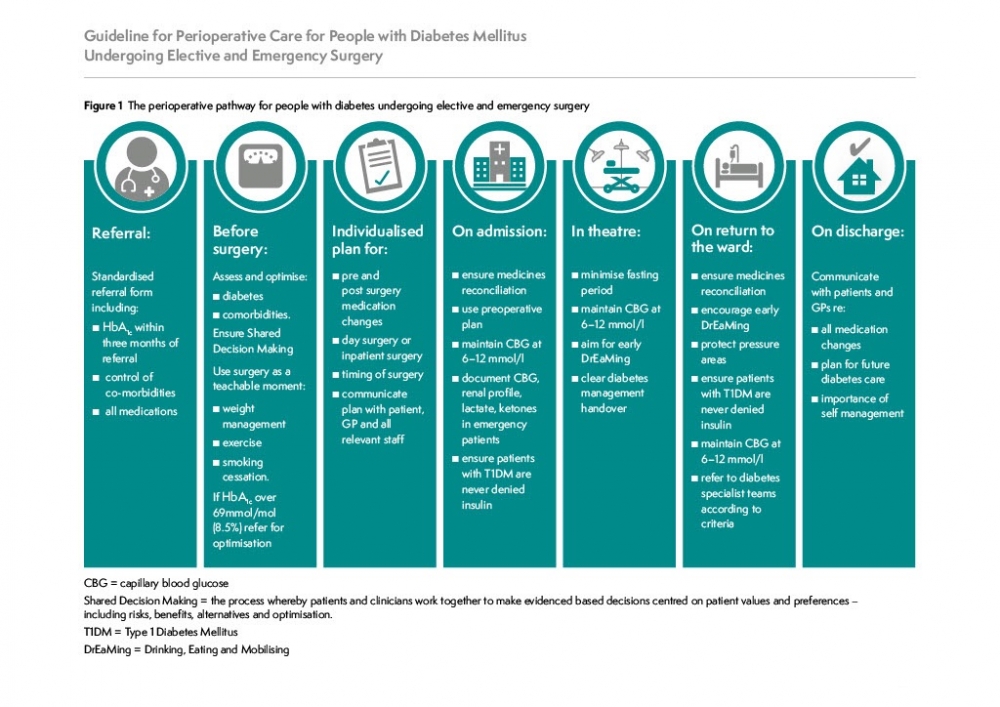

The document is comprehensive, and there are sections describing the ideal pathway from primary referral through to discharge and is summarised in the figure;

In addition to sections discussing the ideal pathway, there are practical resources. For example, there is explicit guidance on safe manipulation of diabetes drugs that will allow patients to miss one meal without resorting to insulin infusions, and without the fear of hypoglycaemia, diabetic keto-acidosis, lactic acidosis, and hyperglycaemia.

The concept of differentiating diabetes drugs into glucose lowering medication and others is discussed. This is because certain diabetes drugs ( eg insulins and sulphonylureas ) work by actually reducing glucose and therefore hypoglycaemia in the starved state is a real concern. With other drugs, whilst they may not predispose to hypoglycaemia in the starved state, they may predispose to other dangerous conditions eg SGLT2 inhibitors and euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. The practical resources discuss the nuances of each drug type.

Repeated national audit has highlighted that hospitalised people with diabetes are prone to three distinct harms:

- Hospital acquired hypoglycaemia

- Hospital acquired DKA

- Drug errors and errors associated with insulin infusions.

The guidance’s aim from the start was the need to implement strategies to reduce the incidence of these 3 common issues.

To reduce the risk of the hospital acquired hypoglycaemia, there is guidance stating that the ideal blood glucose zone is 6-10mmol/l, and that a blood sugar of 4-6 mmol/l (especially if the patient is on glucose lowering medication) should be treated to prevent “looming hypoglycaemia” transitioning to actual hypoglycaemia ( CBG <4mmol/l), which carries an increased risk of death and harm.1

To reduce the risk of hospital acquired DKA there is explicit guidance on the need to check ketone levels with a ketonemeter if the CBG is >13, and that ketonemeters need to be available in every clinical area. There is also detailed advice that patients with type 1 diabetes should never be denied insulin and that the long acting basal analogue should be continued, albeit at 80% of the usual dose.

To reduce the risk of drug errors it is recommended that medicine reconciliation occurs ideally even prior to admission.

To help ensure all of these processes occur, it is recommended that there is a clinical lead in every hospital supported by a perioperative diabetes inpatient specialist nurse.

This document is an electronic document, and this will allow and facilitate changes to be incorporated annually as required. Feedback is encouraged to @CPOC_News

Download and read the full guidance document